Hawai’i: Food as a Bridge to Harmony

Sunday, September 29, 2013 at 7:00PM

Sunday, September 29, 2013 at 7:00PM

Congrats to Serena C. from Boston, MA, who wins a copy of Melissa’s 50 Best Plants on the Planet.

By Sandy Hu

The latest from Inside Special Fork

A century ago, a simple, two-tiered metal lunch bucket became a catalyst for helping polyglot immigrant workers find common ground in the sugarcane fields of Hawai’i. It nurtured the harmonious culture and cuisine enjoyed in the Islands to this day.

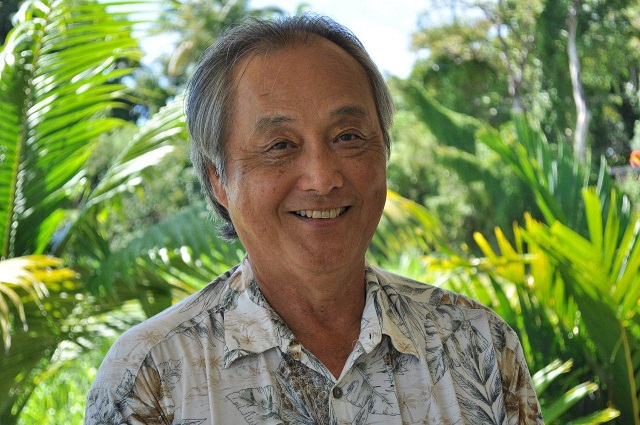

Last week, I sat down with Arnold Hiura, journalist, author and historian, in our plantation-style vacation rental built on former sugarcane fields on the Big Island of Hawai’i, to hear this fascinating story. It’s especially significant for me, because all four of my grandparents emigrated from Japan to become sugar plantation field hands. After their work contracts expired, the Honda side of the family moved on to coffee farming, while the Matsukawas continued to raise sugarcane.

THE IMMIGRANT EXPERIENCE

It must have been a traumatic and bewildering experience for the plantation workers – primarily Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipino, Puerto Rican and Korean – thrown together, despite different cultures, customs and languages. But eventually, lunchtime bridged the divide, as Arnold explained.

When the lunch whistle blew, everybody stopped work and had lunch in the fields with their multi-ethnic work gangs. The workers squatted in a circle, wherever they happened to be, and opened their lunch bucket, a two-tiered metal container with a carrying handle.

The base, the larger of the two containers, held the rice. The top tier held the okazu, the Japanese word for a dish to accompany the rice. For these poor workers, no matter what country  they came from, rice was really the main part of the meal and the okazu, what we would consider a main dish, was served in small amounts, simply as a flavoring for the rice, according to Arnold.

they came from, rice was really the main part of the meal and the okazu, what we would consider a main dish, was served in small amounts, simply as a flavoring for the rice, according to Arnold.

“You put the okazu container in the middle of the circle and held on to your own rice,” Arnold said. “Whether you liked it or not, you ate a little of everyone’s food. In this situation it’s a lot more awkward not to try (someone else’s food), than to eat something you didn’t care to eat. It may look funky or smell a little strong, but you tried it. And in the process you might really get to like it.

“It was also an interesting exercise in social graces,” Arnold added. “You had to learn when to take food from the circle, how much it was acceptable to take, and not to take too much.”

By sharing, the plantation workers became familiar with each other’s food and formed social bonds. Exposure to the wide variety of ethnic foods evolved into the mixed plate lunch, takeout meals locals continue to enjoy today that might include Portuguese sausage, Korean kimchi, macaroni salad and Japanese tempura, all on the same plate. And of course, the requisite two scoops of rice.

Arnold described the plantation food experience in his first book, Kau Kau, Cuisine & Culture of the Hawaiian Islands. He followed that book by co-writing with Hawai’i’s master chef and James Beard Award winner Alan Wong, The Blue Tomato: The Inspirations Behind the Cuisine of Alan Wong. Both books were published by Watermark Publishing. A third book, From Kaukau to Cuisine, Island Cooking Then and Now, is underway.

FOOD AS A METAPHOR

Arnold’s interest in food and food history was acquired in a circuitous way. A former editor of the Hawai’i Herald newspaper, Arnold was well into a thriving freelance writing business when he was approached to be the Hawai’i-based curator for the Japanese-American National Museum in Los Angeles to spearhead acquisitions and develop exhibitions featuring the Japanese experience in Hawai’i.

He worked on a major traveling exhibition, From Bento to Mixed Plate: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Multicultural Hawai’i, that filled two-and-a-half Matson container loads. The  exhibition was shown throughout Hawai’i, in Los Angeles and at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. A Japanese version toured Japan.

exhibition was shown throughout Hawai’i, in Los Angeles and at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. A Japanese version toured Japan.

Arnold became fascinated by the stories behind the objects. “Food happened to be a usable metaphor as an entrée to understanding the immigrant experience,” Arnold said. It exemplified the multicultural aspects of people in Hawai’i – an acculturation so different from elsewhere in the United States where the process was often more rocky and less complete.

FOOD CHOICES AND ECONOMICS

He shared another key insight. “What a lot of people overlook is the important role economics played in determining what we ate,” Arnold reflected. “The plantations had all these different ethnic groups but people ate very similar food – what was available and what was affordable.

“We have fun with Spam, but why Spam? It was indestructible, affordable, required no refrigeration and was heavily salted. You could chop it up and cook it with a whole pot of cabbage or onions, season with soy sauce, sugar, garlic and ginger, and serve it with a big pot of rice to feed a family of ten.” This was true of all the canned proteins – canned sardines, Vienna sausages, deviled ham, tuna and corned beef, he added.

Food trucks are trendy and all the range these days. “But in Hawai’i, lunch wagons go back decades,” Arnold said. “It wasn’t a fancy culinary experience. It was blue collar, fill your belly and cheap. The lunch wagons parked near surf spots, construction sites and by the wharf for stevedores. It had lots of rice and gravy. I love the old lunch wagons.”

THE FUTURE

Arnold’s upcoming book is a collaboration with Derek Kurisu, Executive Vice President of KTA Superstores (a family-owned Big Island supermarket chain), who will look back at some of the classic traditional dishes of Hawai’i, while Jason Takemura, Executive Chef of the Hukilau and Pagoda restaurants in Honolulu, provides the contemporary insights.

“Part of the story is reflecting on the food influences of the past and looking at contemporary trends and where food is headed, as well as the connections between past and present. Those connections are still strong,” Arnold observed.

“What’s old is new again,” he added, as he ticked off some of today's hot trends: using the whole animal from tongue to tail, grass-fed beef, farm to table, foraging, smoking meats – all these trends have roots in Hawai’i’s past. This foundation, along with new and experimental methods of cooking, new ingredients, attention to health-consciousness, the infusion of more recent immigrants adding new ethnic influences, and the creativity of every young chef ready to put their own twist to the traditional legacy foods, will bring about the vibrant cuisine of the future, he said.

Here is a Portuguese recipe from Kau Kau, Cuisine & Culture of the Hawaiian Islands, published by Watermark. Photo of the dish is by Adriana Torres Chong, from the book.

To get the recipe and shopping list on your smartphone (iPhone, BlackBerry, Android device) or PC, click here.

Vinha D’Alhos

Serves 6

3 pounds boneless pork

1-1/2 cups vinegar

2 cloves garlic, crushed

6 Hawaiian red peppers, seeded and chopped

1 bay leaf

2 teaspoons salt

6 whole cloves

1/4 teaspoon thyme

1/8 teaspoon sage

2 tablespoons salad oil

Cut pork into 2- X 1-1/2-inch pieces. Combine vinegar, garlic, red peppers, bay leaf, salt, cloves, thyme and sage; pour over pork and let marinate overnight in refrigerator, stirring 2 or 3 times.

Put pork, with marinade, in pot and cook for 20 minutes over medium heat; drain. Heat oil in skillet; add pork and sauté over low heat for 10 to 15 minutes until browned.

Recipe from Kau Kau, Cuisine & Culture of the Hawaiian Islands by Arnold Hiura; photo by Adriana Torres Chong. Published by Watermark.

Special Fork is a recipe website for your smartphone and PC that solves the daily dinnertime dilemma: what to cook now! Our bloggers blog Monday through Friday to give you cooking inspiration. Check out our recipe database for quick ideas that take no more than 30 minutes of prep time. Follow us on Facebook , Twitter, Pinterest, and YouTube.

Related posts:

Special Fork |

Special Fork |  1 Comment | tagged

1 Comment | tagged  Arnold Hiura,

Arnold Hiura,  Hawaiian food,

Hawaiian food,  Hawaiian immigrants,

Hawaiian immigrants,  Kau Kau Cuisine & Culture of the Hawaiian Islands,

Kau Kau Cuisine & Culture of the Hawaiian Islands,  Portuguese pork dish,

Portuguese pork dish,  Portuguese recipe,

Portuguese recipe,  Special Fork,

Special Fork,  Vinha D’Alhos,

Vinha D’Alhos,  Watermark Publishing,

Watermark Publishing,  food blogs,

food blogs,  mobile recipe website,

mobile recipe website,  sugar plantation workers in

sugar plantation workers in  Inside Special Fork

Inside Special Fork

Reader Comments (1)

Love the recipe, I can't wait to cook this as soon as possible. Thanks for sharing such an delicious dish with us...